lo selzga homepage of mike richman

my backstory

When I was ten years old, my grandmother gifted me a computer, and it was the most influential present of my life.

This was 1995. We’re talking about a 25 MHz 486, presumably at least several megs of RAM. MS-DOS six point something and Windows 3.1. It was just enough to play DOOM, but not enough to eventually play Quake (the 486 was missing the math coprocessor). It was enough for writing trivial programs in QBasic.

Code seemed to offer a world of endless possibility. In those early years, I can’t say I implemented anything of note. Perhaps the most fun I had was writing a counter-printing infinite loop on an Apple IIc during some downtime in class. The important bit was just knowing that you could make the computer do the thing.

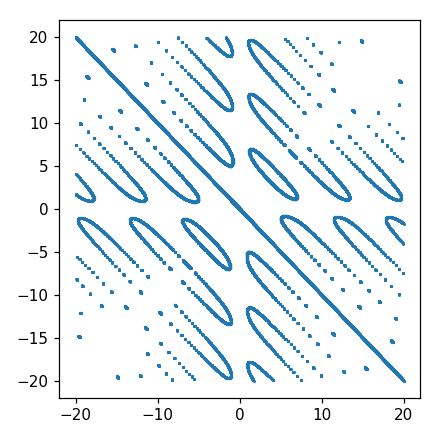

My first genuinely interesting project was probably DerfCalc1, which I wrote in collaboration with a friend. This was a graphing calculator that broke free from the restrictive world of functions, allowing the user to plot general 2D relations. For example, one of our favorites was:

\[x\cdot y\cdot\sin(x+y) = x+y.\]We used Visual Basic 6 for the user interface, and QBasic as the math backend

— we were far from being able to parse expressions programatically. The

plotting code was entirely custom, starting from a raw DrawingArea or

something like that. With quasi-pirated copies of VB and virtually no

guidance, this was apparently the most direct route to our goal of visualizing

arbitrary 2D relations.

Today, we can achieve the same goal in just a few lines of Python:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

x = y = np.linspace(-20, 20, 5000)

X, Y = np.meshgrid(x, y, indexing='ij')

z1 = X*Y*np.sin(X+Y)

z2 = X + Y

mask = np.abs(z1 - z2) < .05

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(4,4))

ax.plot(X[mask].ravel(), Y[mask].ravel(), '.', ms=2)

My high school didn’t particularly support my coding habit, but it had science classes. Biology/Chemistry/Physics/AP Physics, each year more interesting (to me) than the one prior.

I didn’t know what to do next, but college seemed like a decent choice. At The College of New Jersey2, I declared my physics major after the first semester. Code remained mainly a hobby. I switched to Linux originally just to prove to my friends that Windows/Mac wasn’t an exhaustive list.

It was handy, though, being able to code. Some courses required calculations or even full-on applications using Fortran, C++, or Visual Basic (by 2006, this meant .NET). I learned Emacs and LaTeX following a tip from the General Relativity professor. My most practical app was a mess of cron jobs and shell scripts that would e-mail our class when a particularly unhelpful professor would post homework problem sets, otherwise unannounced, to his handwritten HTML web page.

I didn’t know what to do next, but grad school seemed like a decent choice. My record on paper looked great, and I got into the University of Maryland, where I promptly got my butt kicked by serious coursework intended for serious students. The level of rigor was multiple notches above that of my small liberal arts college background. I switched from Emacs to Vim.

Studying hard got me through required coursework and the written qualifier, but that wasn’t enough for a Ph.D.; I needed to start doing research. Fortunately, a required Grad Lab course taught me that data is awesome. I saw a flier about an opening in a group with something something the South Pole something neutrinos something data, and I met with the professor.

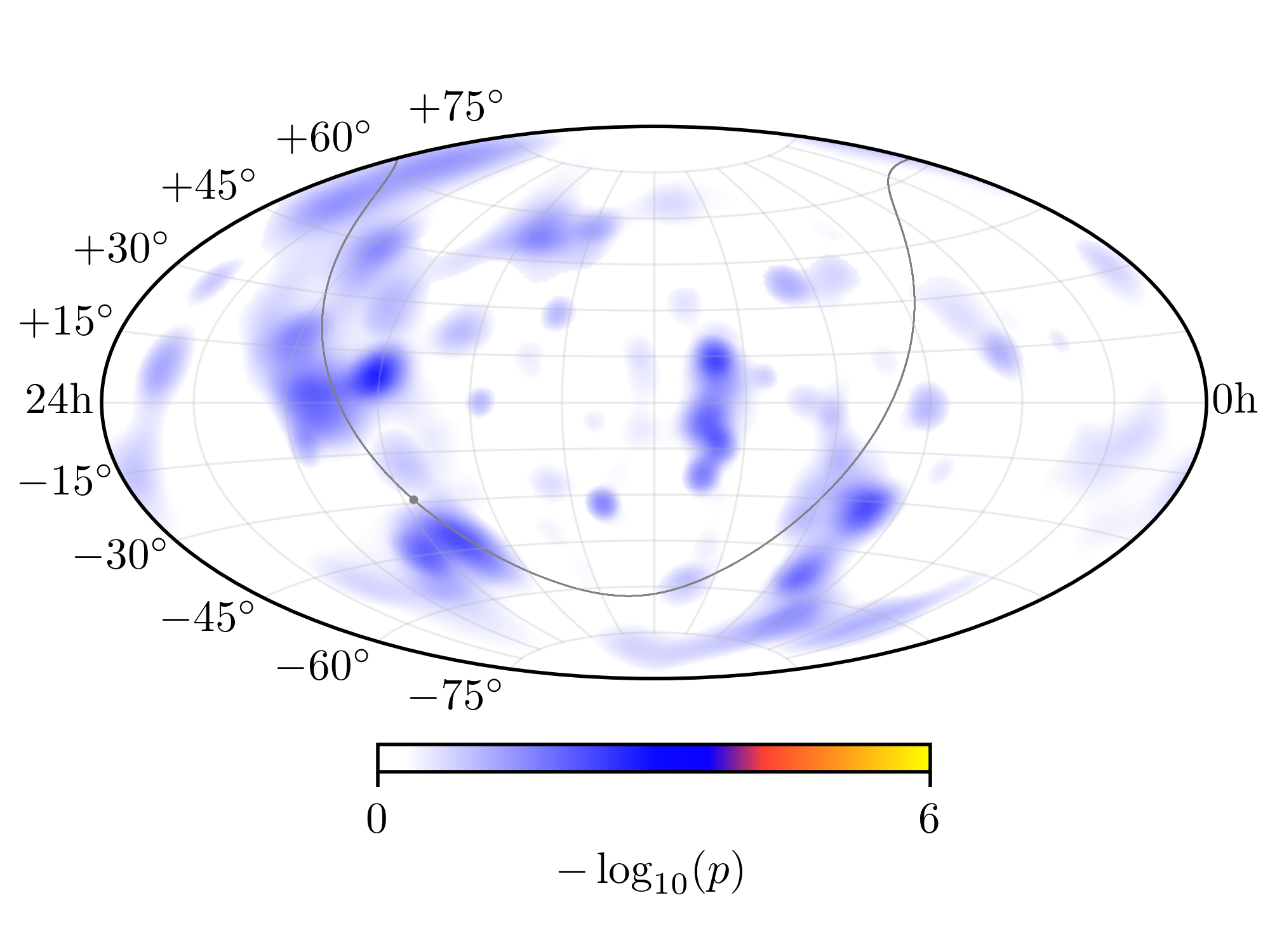

The first project, featured on the flier, involved some alpha-level hardware attached parasitically to parts of the main experiment, which was called IceCube. It turns out that this was an absolutely incredible observatory, run by a wonderful hundreds-strong collaboration distributed over dozens of universities in many countries across several continents.

I learned and fell in love with Python, keeping C++ in my back pocket for performance-critical inner loops. I learned statistics kind of in reverse: starting with frequentist maximum likelihood methods, going back for $\chi^2$ and Poisson statistics and eventually Bayes’ theorem. I wrote my own boosted/random decision tree forest library in 2010, before scikit-learn supported weighted training samples (critical for high energy particle physics). I demonstrated that gamma ray bursts (GRBs) usually don’t make high energy neutrinos when they make gamma rays. This last bit was enough to write a decent paper and a solid Ph.D. dissertation.

I didn’t know what to do next, but a postdoc seemed like a decent choice. During my last semester at UMD, it came to my attention that a certain former postdoc had become a professor at Drexel University. I hit her up on our brand-new Slack server. She opened a position, I applied, she officially offered me the job, I accepted.

The deal was: let’s start an IceCube group together. There were students to mentor and analyses to perform. I taught statistics to the best of my ability. We started graduating students. I performed analyses leading to a couple of papers.

Along the way, I dove deep into the numpy/scipy/matplotlib stack. I drafted my own histogram library called histlite as well as additional IceCube-internal packages. I met my fiancée, who taught me that even condensed matter physics is interesting if there’s data.

After years as a postdoc, this time I finally knew what to do next. I started applying for Data Scientist positions3.

Every step is pain. At first you don’t even have a résumé. You write one and start sending out applications, but you rarely hear back. You make some adjustments, and phone screens start coming. Some of these lead to technical calls, which you bomb. You read up on interview techniques, continue to tweak the résumé, and keep spamming the world with applications. Phone interviews start going better, and invitations to do data exercises start coming.

I never really needed machine learning beyond the aforementioned RF/BDT library. Never even really needed Pandas, for that matter. Literally what even is NLP? Every data exercise was a crash course in something.

So you Google a lot and send your notebooks in. You learn a ton along the way. At first they say, “we’re going with someone with more (relevant) experience.” And then eventually, at long last, you get to on-site interviews.

All of them go well; now it’s down to the specific companies. Sure you can code, but can you solve business problems? Some think “yes” — you finally get a couple offers. You read about salary negotiations and give it a shot.

Or more likely, it’s completely different for you, but that’s how it went for me. I accepted an offer and I start this Monday.

-

Derf was my nickname because it is Fred backwards. No, “Fred” is not in any way my name. High school nicknames are weird. ↩

-

The “The” is officially a capitalized part of the name. ↩

-

This is my experience searching for jobs exclusively in Philadelphia — things can be very different elsewhere or in a less geographically-constrained search. ↩